Scott Holmquist's “chronic freedom” Series

Cannabis growing for the future alien peasant

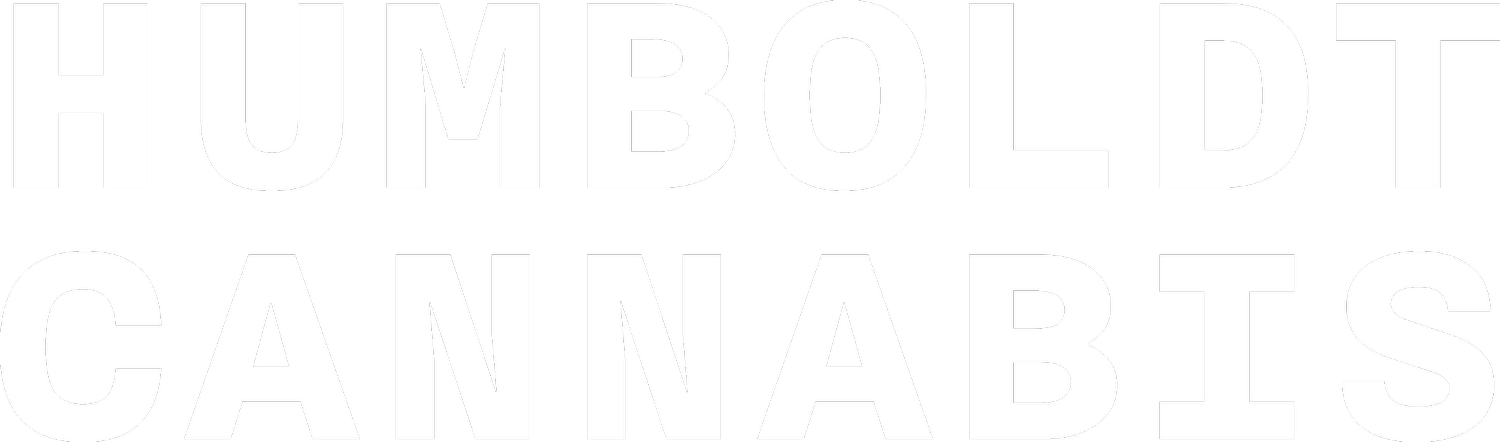

Clockwise from top left: Big Drug Factory – Unfound; 3 books; chronic freedom; 3 books.

Photographs by Scott Holmquist Studio©

Be forewarned: these books are not going to fit neatly on your shelf, sandwiched in there between the Cannabis Grow Bible and What’s Wrong With My Marijuana Plant? These books need their space. They demand your attention and sometimes your full-body participation.

When I viewed these volumes at Bug Press in Arcata recently, by special arrangement, it felt a bit as though a social revolutionary with the Situationist International had traveled forward in time, juking improbably from Paris 1968 to Garberville 2010, producing a radical archive in codex form along the way. Collaged together from reproductions, photos and text, framed by original writing, these books document community loyalties, political viewpoints, musical selections, conversation styles, slang and assorted intangibles of the cannabis-growing scene that emerged in Southern Humboldt in the 1970s and 1980s. They represent, in their maker’s words, “a unified attempt to survey, collect and interrogate traces of the histories comprising the back-to-the-land and marijuana production worlds as they evolved in Southern Humboldt County, Calif., from the late 1960s through 2010.

Clockwise from top: 3 books; light; dirt; Big Drug Factory – Unfound; chronic freedom.

Photograph by Scott Holmquist Studio©

Holmquist conceived the books to exhibit in private spaces among the people who are its subjects, which he has done in more than a dozen presentations since 2011, nearly all at remote homesteads. The main volume’s opening essay, “Against Dialogue: for speaking only to ourselves” explains: “This book is for you if you are of, or related to, the communities of SoHum hippies or hippie-sympathetic pot growers — past, present and future.” In fact, I am the first outside writer allowed to view them, though not in their intended site-specific installation.

dirt has big, crackling, brightly colored pages made from soil amendment bags bound in covers made from tent-canvas and rubber bed-liner scavanged from a defunct indoor grow on Reed Mountain. It has pages nearly 3 feet tall; unless you have exceptionally long arms, you read it standing up. 3 books features luxuriously poofy cream-colored leather binding, embossed with an artfully rendered cannabis bud based on a woodcut by illustrator and Southern Humboldt painter Frank Cieciorka, best known for the clenched-fist salute graphic that became the emblem of radical 1960s movements.

Much of the printing was done by Bug Press. Minnesota-born Holmquist, who has lived in Berlin, Germany, since 2011 but keeps an office in Arcata, made the originals at his studios in Eureka and Berlin. The books bring together a host of rare primary sources in reproduction: transcriptions of interviews and chat room exchanges, musical samples, 40 years of programs from community center events, bills for hip-hop shows, and reproductions of mimeographed magazines produced by SoHum back-to-the-landers from the 1970s through the 2000s.

chronic freedom

Photograph by Scott Holmquist Studio©.

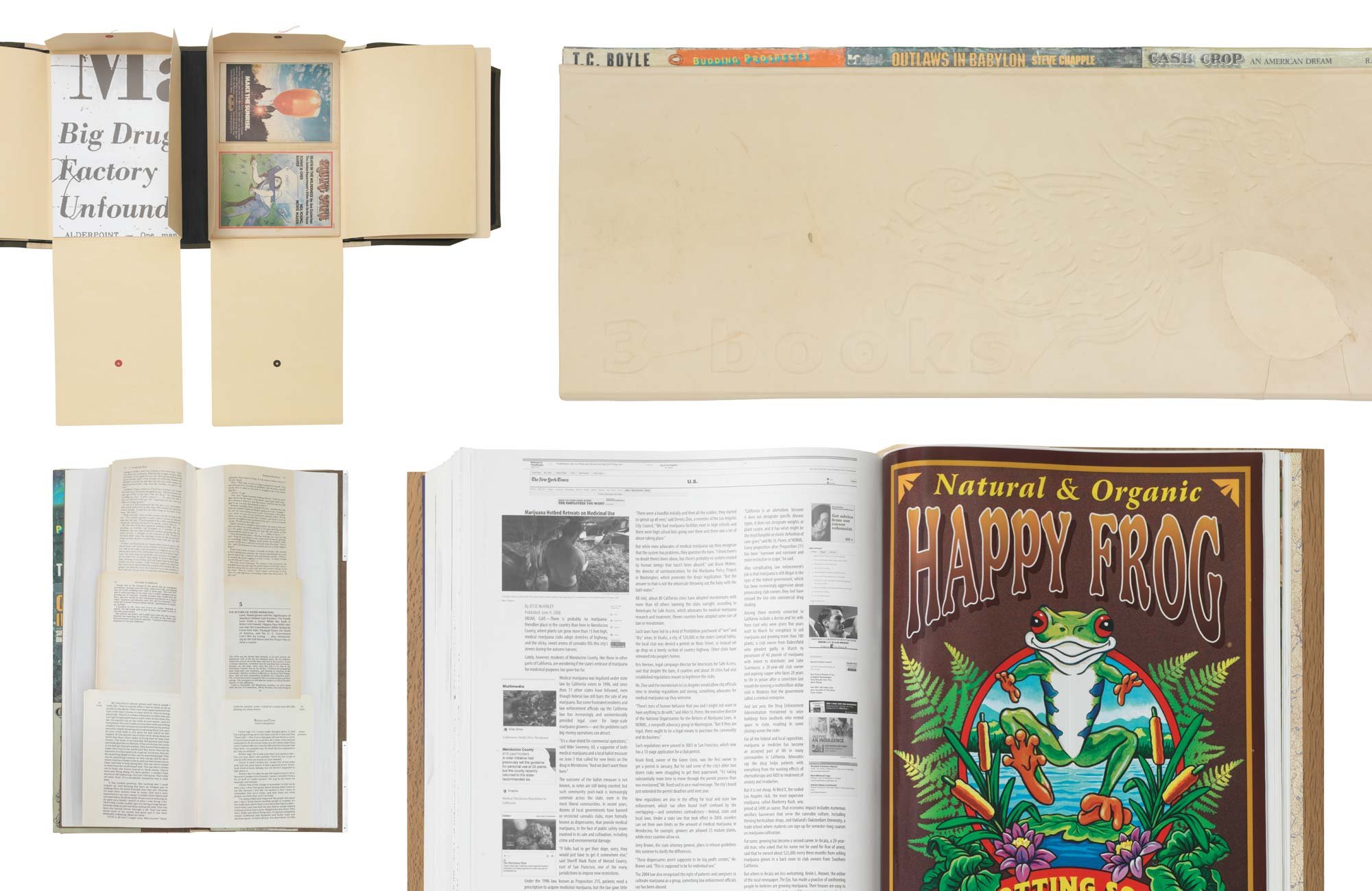

Materials you wouldn’t necessarily think of as being booklike rasp and rattle as you turn these pages. This is serious ephemera: promo stickers and audio cassette art inserts, flattened bullet slugs resting inside the book’s pages in custom-cut vaults, tarpaulins and bags for local soil mixes like Happy Frog and Ocean Forest, turkey bags still littered with bud residue, all painstakingly bound to the volume’s spine with polyethylene drip line. You can almost smell the pungent perfume of a trim scene wafting off these pages.

Materials lists give some idea of the intricacy of these volumes’ construction. dirt is “inkjet-printed in color on adhesive paper bonded to soil and soil supplement bags, cut open into bi-folds and side-stitched, hand bound to rusted ½-inch rebar spine and covered with tent canvas and pond liner scavenged from marijuana-growing operations.” Meanwhile, chronic freedom is “partially encased in calfskin attached to oak panels with titles of steel letters. In three of the book sections, fired bullet slugs have been set into niches carved into pages.”

Most volumes adopt the form bookbinders call a codex — a sequence of pleated pages between covers. All push against the format’s expected norms. While the books contain printed components, they have more in common with handmade manuscripts than they do with the average trade paperback. Small wonder that little figures from medieval illuminations appear throughout the pages of chronic freedom, popping up to tend gardens, roll barrels, sing, dance and otherwise carry on among the marginalia.

The more than 1,000-page omnibus that is chronic freedom includes three sections of pages that have nothing to do with the traditional purpose of supporting text. They function more as a medium for sculpture, accommodating precision cuts that form small secret compartments within the book, slicing through the massed pages the way a worm tunnels through a tree’s concentric rings. The shapes of these “bullet vaults” repeat the irregular curves of the handcrafted slugs they contain.

The chronic of the title refers both to the complexities of growing-life freedoms and South Central Los Angeles slang for Humboldt-grade cannabis that also provided Dr. Dre’s 1992 album title, The Chronic, among the most critically and commercially successful CDs of the 1990s.

light, the most sculptural object of the bunch, takes the form of a scroll suspended from two busted EYE 1000-watt high-pressure sodium-mercury bulbs, with their amalgam arc-tubes intact, once used to light an indoor grow.

Big Drug Factory – Unfound blurs the lines between book, archive, and archive tool: its four-flap canvas and leather sheath and multi-flap archival folders exist to protect and encompass its contents. A 13-page tabloid-form book is in one of two archival folders set next to each other. The contents of the second turn out to be (surprise!) another text — specifically, an original copy of Rolling Stone from May 24, 1973, the one with a cover story by Joe Eszterhas, “Death in the Wilderness: The Justice Department’s Killer Nark Strike Force,” which was the first account of drug-war life and death in Southern Humboldt to hit the national press. The book takes its title from a Eureka Times-Standard front-page headline in 1972 that began, “Man Killed in Raid, Big Drug Factory – Unfound.

3 books features three smaller volumes reassembled into one book’s binding, vertically superimposed end-to-end — its a literal book of books, like a stacked series of nesting dolls. The three paperbacks in question Holmquist describes as the three earliest book-length accounts of U.S. cannabis production — T.C. Boyle’s Budding Prospects, Steve Chapple’s Outlaws in Babylon and Ray Raphael’s Cash Crop: An American Dream, all published 1984-85, retitled by Holmquist in his book as Pastoral, Gonzo Report, and Self-Portrait.

This gonzo presentation has its advantages. The opportunities for comparison it generates can be instructive — when sources are matched up this way, the art of storytelling becomes apparent. The eye tends to hover, comparing and contrasting, skipping from one text to the next as it moves across the page. At times this makes the reading experience feel like a three-way version of the cut-up technique credited to English artist Brion Gysin in the 1960s, in which a text is literally quartered and then reassembled to reveal its potential for meanings other than those which the authors originally intended.

Gravid bodies, hidden cavities, nesting units and mise-en-abyme effects — books opening to reveal other books, paintings of paintings — are everywhere.

Holmquist presenting dirt at a private viewing in Petrolia.

Photo by Tony Smull

When I caught up with Holmquist, speaking from Berlin, the artist was eager to discuss the archival approach he adopted to support original texts in the books. “I sought to gather traces of the histories and their different tellings, accumulating all documents on the subject I could find,” he told me. And he accumulated these impartially. “Whether it was small notebook drawings people made or watershed diagrams, or publications like Gulch Mulch, I included them. Every page of local items, some I micro-printed, set against, for instance, a 1983 article about growing in Southern Humboldt from People magazine … interested in bringing out the inevitable ironies and contradictions among the completely different points of view within these things set next to one another.”

He has deliberately made no attempt to explain the materials he amassed. “I wanted to avoid distorting the things themselves with explanations that often depend on mainstream concepts. With the lived knowledge of growing, meanings fall together and offer pleasurable surprises,” he said. I asked if he sought to tell the real story and he said, “I wasn’t interested in ‘telling the story,’ or writing the history, or seeking to be impartial. In fact, this work is partisan, for the hippie and activist grower communities … And I did not pretend that I could include all voices.” Indeed, women’s voices and experiences in the Southern Humboldt cannabis scene seem to be underrepresented, though there are several lengthy interviews of founding and first generation back-to-the-lander women, whom Holmquist had interviewed by Jennifer Block, a journalist and author friend. I also did not find anything on the presence of Hmong, Lao and Thai workers in Southern Humboldt, perennially underreported, though given the number of pages and documents, often reproduced in microscopic printing, I cannnot be sure they went unmentioned.

The volumes avoid the region’s most stereotypical endemic narratives, correcting instead for the lurid and exploitative portraits of Southern Humboldt that some visiting journalists have drawn. They juxtapose accounts from a variety of voices: government surveys of the hills’ topography, AOL chat room wars, tabloid exposés, police reports, 1970s self-produced folk cassettes and 2000s hip-hop CDs. The groovy hippiespeak of the county’s little magazines butts up against the Babbitty tone of small-town newspaper accounts, then against the breezy and propulsive lingo of New Journalism. Readers explore by picking their way through the texts, moving forward or backward according to the moment’s dictates.

Holmquist has imagined his books functioning as time capsules or “core samples” of the “insurgent communities” that laid the foundations of the Humboldt cannabis economy and its attendant cultures, building schools and institutions like a credit union and health center, all over a certain span of time, now beginning to recede into the past — a time when the cannabis-growing communites were concentrated in Southern Humboldt and Northern Mendocino counties, when they were more close-knit, self-sufficient and politically active, bound by their shared illegal livelihood. “If these books were somehow, in some future, the only evidence of what happened in those hills,” he mused, “if we could project the material into the distant future, when it’s discovered by the peasants of some different world, what would we learn?” His beautifully constructed volumes are built to last. Thanks to their material integrity, who knows? The future’s alien peasants might just get their chance.

One of the artist’s remaining copies of the chronic freedom series has been donated to Cal Poly Humbold’ts new Special Colleciton room. Holmquist presented his work in person in 2018.